Terminal Performance in Muzzleloading

Prior to writing this article, I received a note from Martin Fackler, M.D., after I had inquired about an easy source for the bulk of Dr. Fackler's research. Dr. Fackler mentioned that of his over 250 articles in print concerning wound ballistics, most were published in medical journals, and were not available under one cover, or even "readily available" at all to the public. However, Dr. Fackler did mention that that he is working on a book that would contain the entire text of his most pertinent papers included as an appendix-but completion of this work was probably a year or more away. As far as I'm concerned, it just can't be made available too soon. Dr. Fackler's work is without peer, his credentials are impeccable, and his scientific approach to wounding both startling, and startlingly good. Dr. Fackler's article, Firearms in America: The Facts. of Monday, Dec. 25, 2000 is a must read for every firearms owner; a "muster read" for all Americans.

A paper from the U.S. Department of Justice of July 14, 1989 written by Special Agent Urey W. Patrick, Firearms Training Unit, FBI ACADEMY, Quantico, Virginia, entitled Handgun Wounding Factors and Effectiveness made no headlines in the muzzleloading community, but perhaps it should have. The conclusions expressed in this US Government Document should startle more than a few-and evoke a rethinking of what our perceptions of muzzleloading hunting and harvesting are. In part, after citing sources and the requisite due diligence, the conclusions in part read:

"The will to survive and to fight despite horrific damage to the body is commonplace on the battlefield, and on the street. Barring a hit to the brain, the only way to force incapacitation is to cause sufficient blood loss that the subject can no longer function, and that takes time. Even if the heart is instantly destroyed, there is sufficient oxygen in the brain to support full and complete voluntary action for 10-15 seconds.

Kinetic energy does not wound. Temporary cavity does not wound. The much discussed "shock" of bullet impact is a fable and "knock down" power is a myth. The critical element is penetration. The bullet must pass through the large, blood bearing organs and be of sufficient diameter to promote rapid bleeding. Penetration less than 12 inches is too little, and, in the words of two of the participants in the 1987 Wound Ballistics Workshop, "too little penetration will get you killed." Given desirable and reliable penetration, the only way to increase bullet effectiveness is to increase the severity of the wound by increasing the size of hole made by the bullet. Any bullet which will not penetrate through vital organs from less than optimal angles is not acceptable. Of those that will penetrate, the edge is always with the bigger bullet."

It is the human animal being referred to, not larger heavier game animals, of course. The observations made are particularly relevant because the discussion is inclusive of inline muzzleloading caliber projectiles, and their performance at common muzzleloading terminal velocities. Strike velocities exceeding 2000 fps from shoulder-fired weapons are not the center of this treatise. Ad-copy and owner's manuals have long reinforced that kinetic energy values are of paramount importance in selecting a load for game. Reading empirical evidence that kinetic energy alone is a very poor indicator of wounding should prove troubling to many. The brags of "knock-down" have been dispelled; it is a matter of physics that a bullets impact cannot knock down an animal any more than it knocks down the shooter. As cited in the article, the impact of a bullet strike is comparative to being it by a baseball.

Consider the often lauded "dropped in his tracks." It sounds impressive, but does not tell us anything about wounding ballistics. We have been taught to think that "down is dead," when down means only down. We think cute buzzwords like "dead right there" are meaningful, when they are absolutely not particularly meaningful or predictable. We place great value on our own experiences, yet our experiences (or wishful recollections of them) are statistically meaningless. We have been taught to worship at the altar of velocity, and think that shooting into newspapers or clay is directly comparable to living tissue with circulation and a rib cage. We are only fooling ourselves, and we have had a lot of help from ad copy and anecdotal evidence to support our self-deception.

"Energy transfer" has been parroted and regurgitated as something of value, and some still believe that a bullet that stays inside an animal is more effective than one that exits. It has been disproved beyond doubt. Living tissue is underestimated, and misunderstood. All animals and all wounds are unique unto themselves, and no bullet wound on game can be identical to the one prior, or the next one. Dog and spear can harvest boar, yet where is our fabulous energy transfer that has been so loudly touted. Arrows can, and have cleanly harvested game-but how much energy IS there to transfer in the first place? We have long heard, and likely have given credence to the "800 fpe to ethically harvest game." Yet, that random number can be achieved with a 25 grain bullet at 4000 fps, or with a 350 grain bullet at 1100 fps. Obviously, there is a difference in what tissue destruction can be obtained, and the size and type of heavy bone that can be obliterated as well with such divergently weighted projectiles. That effectively dismisses the 800 fpe figure, alone, as the only meaningful value.

It is important for me to mention that forensic laboratory tests that have clinically disproven the conventional acceptance (and reliability) of "kinetic energy," "knockdown," frangible bullets, worship of velocity, and exposed the relative unimportance of temporary cavity are not my revelations at all. We all owe a debt of gratitude to Martin L. Fackler, M.D., and his colleagues, for their work in defining what is really important in wounding, and also what is actually a collection of urban legends and myths. If this article sounds like a bit of a downer so far, it really shouldn't-- muzzleloading projectiles can be on splendidly solid ground; and often are.

The quickest way to harvest a deer or other game animal is a bullet through the brain. That is unlikely to become an increasingly common practice, as the small kill zone does not give much margin for error in the hunting fields, and we all want pretty trophies. Posing with a deer with half of a skull or a blown off rack is something few of us seek, yet that is the fastest way to kill a deer however distasteful one may view this.

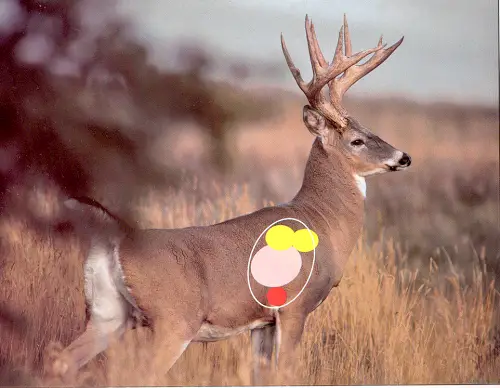

Animals of course move, feed, and change direction when don't want them to. The wind blows our relatively poor ballistic coefficient bullets around as range increases, and the likelihood of precise shot placement diminishes with increasing time of flight of our hunting bullets. Fortunately, a deer offers a very generous vital zone, as shown in Ian McMurchy's picture:

The goal is to destroy as much vital tissue as possible, and cutting, crushing, stretching are the ways in which we do it. Cutting, as demonstrated by knife, spear, and arrow is the most efficient way to destroy tissue. Cutting and crushing is what muzzleloader projectiles can do, with stretching (temporary cavity) of relatively little value due to the elastomeric properties of living animal tissue.

Large caliber bullets automatically crush a lot of tissue compared to their small bore counterparts. Whether a .25 caliber bullet expands to .45 caliber when it breaches the animal's hide, or we are using a .45 caliber bullet makes no great difference to the permanent wound cavity assuming the same penetration-a big permanent hole is just that, regardless of how it is formed. As cited above, penetration is the first consideration in muzzleloading bullet selection. A lumbering pure lead sphere that forms itself into a hockey puck on impact does us little good if penetration is inadequate to destroy vital tissue. I've seen enough "pre-shot" animals to believe this beyond doubt.

We ask a lot of our bullets, and we expect them to perform at unique ranges, on unique animals, and with unique wound paths. A raking or quartering away shot requires more penetration than a broadside shot, and we need a far tougher bullet to penetrate if we are breaking large bones rather than slipping a bullet through ribs, or just nicking the sides of them. It just makes good sense to prepare for the most demanding of scenarios we can fathom when harvesting our game. We are fortunate in that we are starting with .45 to .50 caliber missiles to start with. A one inch hole through our animals' vitals is preferable to a .45 caliber hole, so a bullet that expands is preferable to one that does not. We cannot tolerate expansion at the loss of adequate penetration. If a bullet fragments, its wounding capability is severely diminished as is its ability to penetrate. Consider that IF we can recover a bullet that does not directly hit bone on a broadside shot on an animal, that bullet is likely marginal at best when we do have to hit bone, or if a quartering away shot that requires more terminal penetration is taken. Recovering bullets from animals is not a good thing at all-a bullet that reliably exits the animal, aside from the resultant blood trail, is the better penetrating bullet.

Thin skin is very rubbery, and energy absorbing. It has been shown to be roughly equivalent to four inches of muscle tissue. If the skin on the far side can stop our bullet from a broadside shot, we may have a problem with angling shots. It takes very little effort to find an angle of bullet entry that requires four more inches of tissue to be destroyed from the picture perfect broadside shot-- that just isn't much. Far from the misguided theory that a bullet that remains inside the body cavity of an animal is the better bullet, the large diameter bullet that always blows right through the animal is clearly the more terminally generous bullet-- and the more reliable bullet for varied conditions and animals. If the bullet stays inside the animal on a broadside shot, then it is clear that we can do far better. Bullet recovery is generally a bad thing, not a goal at all that we need or should seek. Dr. Facker's research makes this clear.

Finite percentage of expansion is not a sure thing at all. Indeed, FBI results show that only 60 - 70% of handgun bullets, at close range and at similar velocities to the terminal velocities of many muzzleloading hunting harvests, expand at all. In the case of a spitzer nosed non-expanding projectile, the bullet invariably yaws 180 degrees inside tissue, exiting base forward from the body cavity.

Rather than name specific bullet types or brands, which I believe most readers of this article are well aware of, a few generalizations can be made for our muzzleloading hunting bullets. A bullet that retains a large portion of its weight is far more preferable to one with poor weight retention due to its necessarily restricted penetration. The 300 grain class of bullets is generally better than the 200 - 250 grain class of bullets, again for the reason of better penetration with or without expansion.

Expansion is preferable to a bullet that does not consistently do so, so long as that expansion does not result in inadequate penetration. A bullet that exits the animal is preferable to a bullet that often does not. Sharp-edged bullets that cut tissue are more efficient at destroying tissue than those that can only crush tissue like a ball-peen hammer. A bullet that completely exits more often than not is more desirable than one that does not. Heavier bullets with restricted (or controlled) expansion coupled with absolutely generous penetration are the best choice for today's muzzleloading hunter under the widest variety of circumstances.

For further documentation and forensic studies, see WHAT'S WRONG WITH THE WOUND BALLISTICS LITERATURE, AND WHY by M.L. Fackler, M.D., as published by the Letterman Army Institute of Research, Division of Military Trauma Research, Institute Report Number 239, dated July of 1987, and let's hope that Dr. Fackler's forthcoming tome is made available to today's thinking muzzleloader.

Comment from Dr. Fackler, 8/06/2005:

I liked your article: it makes many good points. The KE fallacy is so pervasive that it needs to be corrected as often as possible. The arrow is a good example: I think it helps to drive the point home if you mention how much KE a hunting arrow has (a 500 grain arrow traveling at 200 ft/sec has a KE of 44 ft lb). Thus the largest game in the world (including elephant) is hunted and killed with a projectile having only about 2/3 the KE of a 22 Short bullet. That should give pause to even the most ardent KE advocates.

M. Fackler

© July, 2005 by Randy Wakeman

Custom Search