Amazing Riflescope Myths

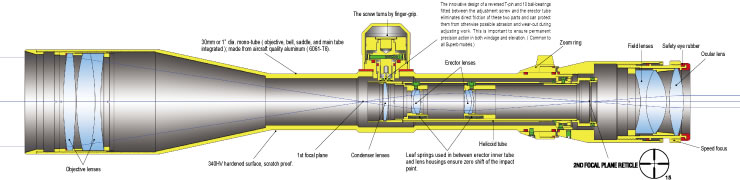

Above, courtesy of Japan Optics, is the First Focal Plane reticle favored in European scopes and found in Pride-Fowler "Rapid Reticle" riflescopes. Below is a representative Second Focal Plane reticle design, sometimes deemed the "American Style."

Bigger Objectives = Better Image

Above, the Swarovski Z6 1-6 x 24mm. Optically superb, this 30mm tactical scope goes for $1850 or so, retains a 4mm exit pupil throughout its zoom range, and you'll note that this optic has what many might think is a diminutive 24mm objective.

Not automatically. With more curvature to a large objective lens, the image is prone to be less clear. As we are bending light, it takes more effort (and dollars) to correct the situation. Well-known as spherical aberration, this is well-covered in Modern Optical Engineering, 3rd Ed., by Warren J. Smith. Further, larger objective lenses weigh more-- a disadvantage in handling recoil. Regardless of objective size, the light is still going to have to travel through a 1 inch or 30mm tube. Monster objectives aren't used in high-end binoculars. The Swarovski 8.5x42 EL Binocular runs $2400 U.S. or thereabouts, has 42mm objectives, and a 4.9mm exit pupil. Image quality remains far more important in a target glassing, locating and acquisition device than in an aiming device. Spherical lenses are used mainly because they are relatively inexpensive to make. Larger pieces of suitable glass for scopes are more costly than smaller ones. For the same dollars, similar price points: we can get better quality, smaller, lower mass objective lenses . . . and better overall hunting scopes as well.

30mm Tubes are Better

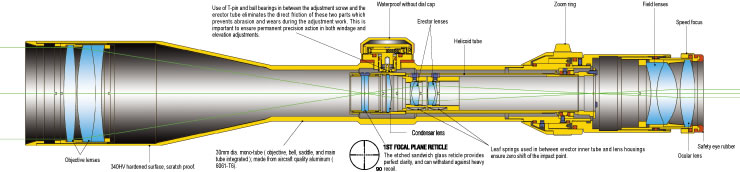

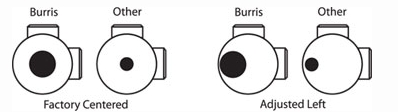

With larger lenses and a larger guide tube in a 30mm scope, you might actually have less adjustment than in a one inch scope. No matter how big the objective, the light still has to focus through the far smaller internal lenses, diminishing the value of larger objectives.

Not necessarily. The primary advantage is they are stronger, far stronger than their one inch counterparts. If the internal lenses are the same size, they can do nothing to flow more light. With larger erector assemblies centered in the tube, they may actually reduce internal adjustment as well. They are stronger, though, some five to ten times as strong. If a riflescope is designed to get the most out of the platform, meaning appropriately large internal lenses, both one inch and 30mm tubes will have very similar internal adjustment ranges.

Lightweight Scopes are Better

Above, courtesy of Hawke Sports Optics, the most popular brand of scope in the U.K. (and the most popular crossbow optic manufacturer in the world), you can see how the relatively ocular and objective lenses make up a significant portion of the weight of a scope: the bulk of scope weight is from the glass. Hawke scopes are able to withstand more recoil than most, exactly what you might expect from a company with its roots in high performance air rifle applications.

Not necessarily. A light weight scope is only lighter in weight, "for sure." The majority of the mass in a riflescope is the glass. More sophisticated lens elements add weight, larger internal lenses may manage light better-- but, weight goes up in concert as well. Stronger, thicker tubes add a bit of weight, as do options like illuminated reticles. More features, more weight, but not necessarily a bad thing.

A Brand of Scope is More Reliable

No, no "brand" is the most reliable. Specific scope models within a brand may well have better track records than others, but internally documented return data is the only evidence of what is and what isn't particularly problematic, and the scope companies won't tell you that. The better companies making running production changes for problem models. Fixed power scopes are the simplest and “suggest” more reliability (two or three less lenses), as do scopes with steel tubes.

For the time it takes to put many thousands of high-powered rounds through a rifle, something hunters don't generally do, speculating whether a scope is "reliable" or not is a waste of time. It is one-incident reporting, margin of error +/- 100%. Q. If you took twenty of the most expensive, well-built, sought-after automobiles in the world, under the worst imaginable conditions, which one would start? A. The one without the dead battery. You can apply this to scopes as well. Q. What scope lasts the longest in the field? A. The one that was mounted properly and not used as a carrying handle. Believe it or not, sometimes scopes are bent or bowed during mounting-- so that factors in along the way, however imprecisely.

Scopes Gather Light

Just as Schmidt & Bender has long published, it is not possible for a scope to gather light. A riflescope can only transmit light. The human cannot detect any difference in light transmission below a 3% variance. Light transmission percentages that are published are often just theoretical. A spectrophotometer can be used to measure light at the objective and what actually exits the scope. Most manufacturers don't bother. It will vary by specific scope model and the number of lenses within that specific scope. You might get the wrongful impression that it is a constant from catalog data, but it is anything but.

Etched Reticles are Weak

Etched reticles are considered the most reliable reticles by most high-end scopemakers, ten times as strong as some wire reticles. That includes $3100 Schmidt & Bender models, Zeiss, Kahles, and so forth. Rather than a mechanical piece of flattened wire, the etched reticle can only be destroyed if you destroy the glass itself. If we really believe that glass cannot be reliable in an aiming device, it might be time to consider going back to iron sights. Schmidt & Bender uses etched reticles in all of their variable power scopes, reportedly the first manufacturer to do so.

An etched reticle requires more attention to detail when it comes to the internal lubrication of a scope, scope purging, and the quality of the black anodizing inside a scope tube. In fact, the tinest speck of dust or anodizing can get caught in the laser engraved surface, proving to be both annoying and distracting. A new scope of lesser quality might appear to be defect-free. Once the erector assembly is cycled, a bit of anodizing or dust can be freed . . . and it invariably finds the reticle. You can take this from folks like Mike Kurtz of Hawke Optics, who evaluates 100 - 200 riflescopes every day.

There is a Best Low Light Scope

No such thing, as many scopes run out of usable reticle prior to losing the ability to target. Humans all have different, unique sets of eyes. We don't see identically, any more we smell or taste things identically. Low light has no precise definition, like "room temperature." No matter how hot or how cold a room gets, it is still room temperature. Reticle choice combined with usable exit pupil (based on our eyes) and at the magnifications we intend to use at our own versions "of low light" are reasonable considerations. Reticle selection is one of the most important factors in scope usability after sunset.

Lead Sleds Are Good for Scopes

Not only are they rough on scopes, the point of impact with Lead Sleds is invariably high compared to shoulder-fired shooting due to the extra muzzle rise. It scales in concert with the intensity of the load. If you want to sight in a rifle for hunting use, your shoulder is the better option. That's the way we tend to use them in the field.

No Fault Warranties Mean Better Scopes

Not at all. It just increases the per unit cost. A lifetime warranty, according to industry insiders, just increases the cost of a scope by about twenty percent. It doesn't improve the scope at all. What tends to improve a scope is tighter quality control and higher rejection rates. The company standards may be high, but most scopemakers rely on sourced parts and someone has to monitor the quality of those vendored parts: meaning reject them or change vendors if needed. Who rejects the most scope components and has the best Q.C. is of course a mystery: both cost money and you can't readily see it just looking in the box. The problem with lifetime warranties are the associated legacy costs. Something like the current "Social Security plan." Generous warranties might make you feel better, the general idea. But the best warranty is still the one that you never have to use.

Scopes Get Repaired

Above, a cross section of the Swarovski Z6: a scope that is certainly worth servicing, if ever the need arises.

Sometimes, but rarely. For mass-produced value-priced to mid-range scopes, often the labor cost of a skilled technician to work through a broken scope is several times the entire cost of new, freshly manufactured product. As a result, often it makes no sense for a manufacturer to overpay to repair a scope, and they don't.

Ballistic Reticle Scopes are Smart

They have their place, but as long as the reticle is constant in size, they are essentially fixed-power scopes, functioning only at one power setting, typically all the way up. Only first focal plane scopes work as hold-over scopes at all magnifications, as in a Pride-Fowler Industries FFP scope. If you know your trajectory and constrain yourself to hold-points and ranges no higher than a big game animal's back, the benefits are not of any practical field advantage for big game hunting.

Adjustment Tracking is Vitally Important

Not always, certainly not in a big game hunting scope. You set it and forget it. There is little reason to fiddle with knobs and clicks when hunting big game. Wait for the right moment, place your shot, then go pick him up. Sighting a scope in, naturally you want adjustments to adjust. The great precision and repeatability of those adjustments has no value unless you are a knob-twirler, something not wanted, much less actually needed, in most big game hunting.

Edge to Edge Clarity is Very Important

Not really, as your aiming point is in the center of the reticle, not at the periphery of the image. Binoculars and spotters are designed for frequent glassing and game location, not riflescopes. Yet, a "good scope" is sometimes designated as good on the basis of how well they are at doing what they aren't designed to do: glassing mountains. As a friend of mine likes to say, if you use your binoculars for three hours, you might use your spotter for fifteen minutes, and your riflescope for sixty seconds.

The Best Thing About a Scope is Image Quality

Not at all. The very best thing a riflescope can do is hold its zero. If it can't do that, it is worthless. Brightness can be over-rated, as a brighter "blob" lacking definition might offer no improvement in your ability to quickly target an object. Some of the most versatile and desirable scopes in the world are not the brightest, as they have more lens surfaces that necessarily reduce light transmission. Note also that some of the finest sets of binoculars made today, like the Swarovski EL, designed to be looked through constantly, have 91% light transmission.

Here is a very common catalog statement: "For optimum image quality, it is important that the optical system of a riflescope deliver as much light as possible to the eye of the shooter. The lighter or brighter the image, the sharper the resolution and the clearer the shot." It couldn't be more wrong. The human eye can only use so much light-- excessive light means squinting and discomfort. No one wears sunglasses because they want more light. a brighter image does not mean it is more clear, it just means it is brighter. A common definition of resolution quantifies how close lines can be to each other and still be visibly resolved. Resolution does not come in sharpness or brightness, it comes in lines. Turning up the brightness of an image does not focus it better, remove abberations or flaws, nor does it automatically increase resolution. Too much light can be a problem, the reason shooters develop cataracts in their shooting eyes first. UV radiation is invisible to the eye and well-documented as being problematic. Riflescopes actually transmit radiation, not just visible-spectrum light.

While certainly the image we think is "better" is better, according to us, the notion of brightness and resolution is overplayed in an aiming device, at least for marketing purposes. Many things help make an image better, control of stray light, flaring, color fidelity, focus. An out of focus image may well be bright, but a blurred image is still a poor image, regardless. A riflescope that holds its zero is better than any scope that doesn't. Other factors, like eye relief, can be far more important than calculated light transmission percentages or theoretical resolution.

Scopes Are Better than Ever Today?

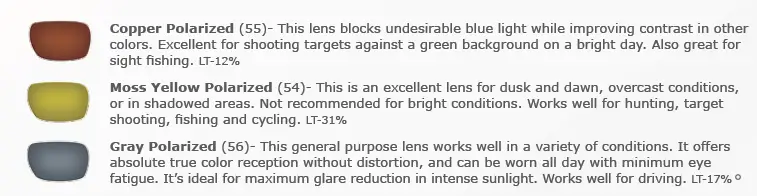

A few of the many choices in shooting lenses from Randolph Engineering, showing light transmission from 12% to 31%.

Quite true. The fully multi-coated riflescope did not appear until 1972 by Kahles. The first American manufacturer to offer fully-multi-coated scopes was Burris in 1980. The "uncoated lens" can lose about 4% of light transmission (per surface). This works exponentially when additional lenses are involved. In a riflescope using six lenses the light transmission may now be 78% (.96*6). Six lense elements fully multi-coated (twelve surfaces) can theoretically hit over 98% light transmission, providing less light losses and better contrast. While the human eye may readily be able to discern the difference between 78% and 90% of visible light, inside the 3% human eye threshold humans cannot tell, although machines can.

There is often too much light as well, the reason our pupils are not constantly dilated. Optical experts agree that the best light transmission range for sunglasses is from only ten to thirty percent, meaning "average" sunglasses may only let through about 1/5th of the light of a quality riflescope. If you wear eyeglasses, are they coated or multi-coated? If they aren't coated, our glasses might have only 92% light transmission, so why are worried about our scope? Note that Randolph Engineering's "Moss Yellow Polarized" lens is not recommended for bright conditions, but is recommended for "dusk and dawn" . . . with a light transmission of 31 percent.

Safety is a Good Reason to Scope your Rifle

Absolutely true. The riflescope is one of the most important safety features you can add to your rifle. It is the last and best chance we have to know what is to the left, right, and behind your target before you fire the bullet that cannot be called back. The DNR departments that prohibit scope use do so at the sad expense of hunter safety.

Glass, Eye Relief, & Parallax

You've likely heard a lot of comments about “good glass,” “better glass,” and “upgraded glass.” Naturally, these are largely meaningless statements. There certainly are well-accepted ways to grade glass, though. You can easily find all the technical information about optical glass you can stand from major glass manufacturers. They include Schott, Hoya, and Ohara. All three make high grades of optical glass that are interchangeable with each other.

What about eye-relief? Sure, no one wants scope-eye, and we all need adequate eye relief for the application. Stated eye relief is only calculated, it varies from person to person. When you focus the reticle on your scope, you move the end of the ocular portion closer to your eye, or farther away. The eye relief of a scope is contingent on how you move the ocular end to focus the reticle for your eyes. One scope called “short” eye relief by one person might well be perfectly acceptable to another. We all adjust our ocular ends a bit differently, changing eye relief as we do so.

Truly constant eye relief doesn't happen, unless you are using a fixed power scope. However, some scopes have more consistent eye relief throughout the zoom range. If the eye relief change is held within three quarters of one inch throughout the zoom range, I'd call that perfectly acceptable. However, we all get to decide how we use our scopes. If, for example, we have a 3-10 scope but only take shots on big game from 3X to 6X, then that is the only area of eye-relief that is relevant. By the same token, if we like the idea of a second focal plane hold-over reticle that only only works at 9, 10, or 12 power, then the remaining eye relief we have at those magnifications is important.

The optical illusion of parallax is always interesting, but at 6X or below is of no great importance. If our eye is in the center of the exit pupil of a riflescope, there is no parallax issue, regardless. Here is the way one manufacturer describes it: “Maximum parallax occurs when your eye is at the very edge of the exit pupil. Even in this unlikely event, our 4x hunting scope focused for 150 yards has a maximum error of only 8/10ths of an inch at 500 yards.” For most big game hunting at moderate magnification levels, parallax is just not an issue.

Links:

http://www.burrisoptics.com/burrisusa.html

Copyright 2011 by Randy Wakeman. All Rights Reserved.